Cardiovascular disease (CVD) encompasses a range of ailments affecting the heart and blood vessels, including coronary heart disease, heart failure, and stroke. Globally, it is the leading cause of death, claiming millions of lives each year¹. A key modifiable risk factor associated with CVD is tobacco smoking. Numerous studies have consistently shown that smokers have a higher risk of developing CVD compared to non-smokers.

The Biological Connection

To understand how smoking elevates cardiovascular risks, it's essential to delve into the biological effects of tobacco smoke on the heart and blood vessels. Cigarette smoke contains over 7,000 chemicals, of which hundreds are harmful, and about 70 can cause cancer².

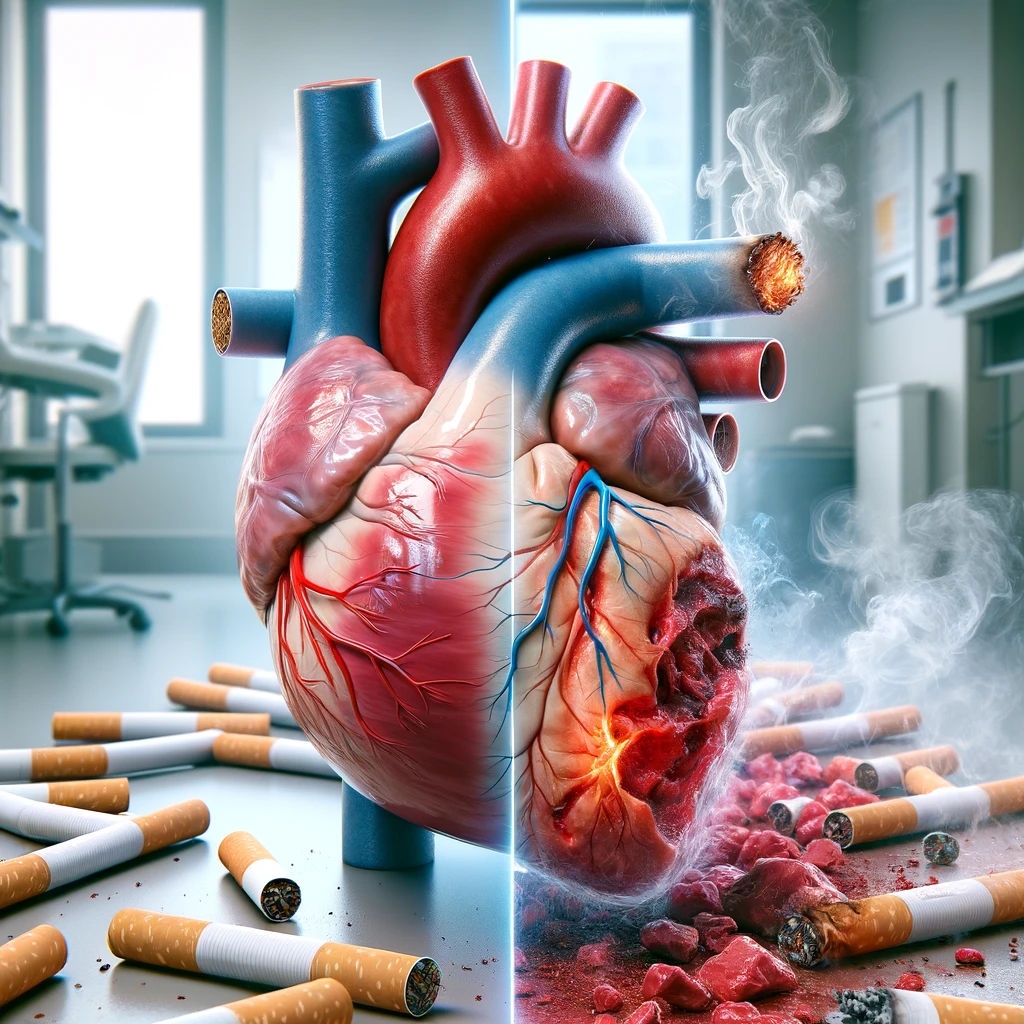

Nicotine, the primary addictive substance in tobacco, raises heart rate and blood pressure³. Additionally, it promotes the release of adrenaline, further straining the heart. Carbon monoxide, another component of tobacco smoke, binds to hemoglobin in red blood cells, reducing the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood. This means that the heart has to work harder to supply the body with the necessary oxygen, increasing the risk of heart disease⁴.

Furthermore, cigarette smoke damages the endothelium (the inner lining of blood vessels), leading to the build-up of fatty materials and the development of atherosclerosis⁵. Atherosclerosis, or the hardening of arteries, is a primary cause of coronary heart disease and can lead to heart attacks. Atherosclerosis itself relates to smoking risks.

Quantifying the Risk

Research shows a clear dose-response relationship between smoking and CVD, meaning the more one smokes, the higher the risk. A landmark study found that smokers are twice as likely to die from coronary heart disease than non-smokers⁶. Another study indicated that even "light" smokers (those who smoke 1-4 cigarettes daily) have a significantly increased risk of heart disease compared to non-smokers⁷.

Passive smoking or exposure to secondhand smoke also carries cardiovascular risks. Non-smokers living with smokers have a 25-30% higher risk of developing heart disease compared to those not exposed to secondhand smoke⁸.

Quitting and Its Benefits

The detrimental effects of smoking on cardiovascular health are undeniable, but the good news is that quitting smoking can substantially reduce the risk. A year after cessation, the risk of coronary heart disease drops to about half that of a smoker's⁹. Over time, former smokers' risk continues to decline, and after 15 years of cessation, their risk approaches that of lifelong non-smokers¹⁰.

Conclusion

Cardiovascular disease's high incidence worldwide can be attributed to various factors, with tobacco smoking being a major modifiable risk. The correlation between tobacco use and CVD has been consistently established through numerous scientific studies. While the immediate cessation of smoking can be challenging due to addiction, the health benefits, particularly concerning CVD, are compelling.

Efforts to reduce the prevalence of smoking through public health campaigns, stricter regulations on tobacco products, and support for quitting resources are critical in combating the global epidemic of cardiovascular disease.

References:

1. World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs).

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General, 2014.

3. Benowitz, N. L. Nicotine addiction. New England Journal of Medicine, 2010; 362(24): 2295-2303.

4. Raupach, T., Schafer, K., Konstantinides, S., & Andreas, S. Secondhand smoke as an acute threat for the cardiovascular system: a change in paradigm. European Heart Journal, 2006; 27(4): 386-392.

5. Ambrose, J. A., & Barua, R. S. The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: an update. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2004; 43(10): 1731-1737.

6. Doll, R., Peto, R., Wheatley, K., Gray, R., & Sutherland, I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 40 years' observations on male British doctors. BMJ, 1994; 309(6959): 901-911.

7. Inoue-Choi, M., Liao, L. M., Reyes-Guzman, C., Hartge, P., Caporaso, N., & Freedman, N. D. Association of long-term, low-intensity smoking with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in the National Institutes of Health–AARP Diet and Health Study. JAMA Internal Medicine, 2017; 177(1): 87-95.

8. Öberg, M., Jaakkola, M. S., Woodward, A., Peruga, A., & Prüss-Ustün, A. Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: a retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries. The Lancet, 2011; 377(9760): 139-146.

9. Critchley, J. A., & Capewell, S. Mortality risk reduction associated with smoking cessation in patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review. JAMA, 2003; 290(1): 86-97.

10. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease: The Biology and Behavioral Basis for Smoking-Attributable Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General, 2010.